Three new realizations are emerging in the government quality profession, that could eclipse and re-structure what we think we know about quality. The new realizations are: 1) That we have missed out on defining a critical part of our essential body of knowledge; 2) That we have overlooked a principal means of tracking the use of quality practice everywhere, and; 3) That we have ignored the best recognized approach to building quality in entire organizations – engaging all front-line managers in its delivery![1] If correct, no wonder we are having trouble sustaining quality in organizations! And also, there is a lot of catching up to do!

This article will present a quick overview of these three realizations along with the assertion that the recently adopted ASQ/ANSI G1:2021 standard will address all of these issues, and that the broad use of ANSI G1 will entirely restructure what we deliver and how we deliver it. It will also present the assertion that ANSI G1 challenges quality professionals to re-think the key practice areas of quality management, and the rigor of their application in order to re-tool the applicability of quality in the future.

First for review is that the “missing major part” of our essential quality practice is found in structured system management and is embedded in the Government Division’s new ANSI G1 standard under the headings of “system maturity” and “system mapping.” While the word “system” is broadly used in quality literature, no one offers a means for its structure or analysis except by suggesting that all system deliverables can be structured and defined as processes![2]

The assertion and belief that systems can (or should) be defined through process analysis is the first major disconnect of quality literature from management reality, and (in the author’s experience) is the largest single reason that quality efforts fail. Where front-line managers do not see benefit to themselves, they do not buy-in, and over time, will push the quality initiatives “out”. Many front-line managers consider process analysis to be either unrealistic or convoluted and argue it does not fit the type of work they are responsible for. We in the quality industry most often hear managers tell us they “don’t have processes here,” and our textbook response is supposed to be “oh yes you do!” When this happens our next textbook response is supposed to be to re-educate them to the wisdom of our ways. And even when we develop really cool data and analysis to teach them, the analytic resources we bring to bear far exceeds what was available to them in their previous work world. In addition, the best-case solutions we develop are often possible improvements those managers were at least partially aware of. In short, they will celebrate with us and are glad to see “us” go, and the use of our quality model grinds to a stop. This kind of quality is an externally imposed event and not an ongoing management solution.

Even our quality frameworks, such as ISO9001 and Baldrige, are imposed top down and are often not often embraced by front line managers as “their own,” and do not have natural sustainability. The failure here is two-fold: We have not built a quality improvement model that front line managers believe in and that they wish to use independently, and on their own. As we will see in a moment, ANSI G1 and its measurable maturity models do present a solution to these issues, but only after we apply the “patch” of structured system management, so that quality practices can easily apply to everyone, and quality management can be applied everywhere in an organization.

While there is an extensive logic for system modeling[3], for now let’s just say that system modeling and analysis is an approach that starts with a cause and effect diagram, and that process modeling is one that begins with a flow chart. This will be further discussed in a moment. Let’s also note that the differences between system and process modeling are reflected in the ANSI G1 standard terms of “tasks” and “actions” (or “activities”)[4]. The “task” designation is used to reference specific work instructions, as are often included in a single process step, while the terms “actions” and “activities” are used to define an output or outcome, with the understanding that its successful completion will depend on circumstances and instructions related to this single cycle of creation.

So for example, a process map anticipates a single path of creation in a controlled production environment and with a single set of output requirements. In contrast, a system map will anticipate a uniform pattern of creation with defined key milestones and check-gates, and with expected flexibility in HOW the value is created based on changing conditions and intervening variables. The system map may also allow for flexibility in output requirements based on small changes in needs. The annual development of an organizational budget document may be one of the best examples of system mapping, because we all know this will require adaptation based on the leader in charge, the kind of fiscal year, and the requirements of political oversight. Carrying out an annual audit plan may be another great example.

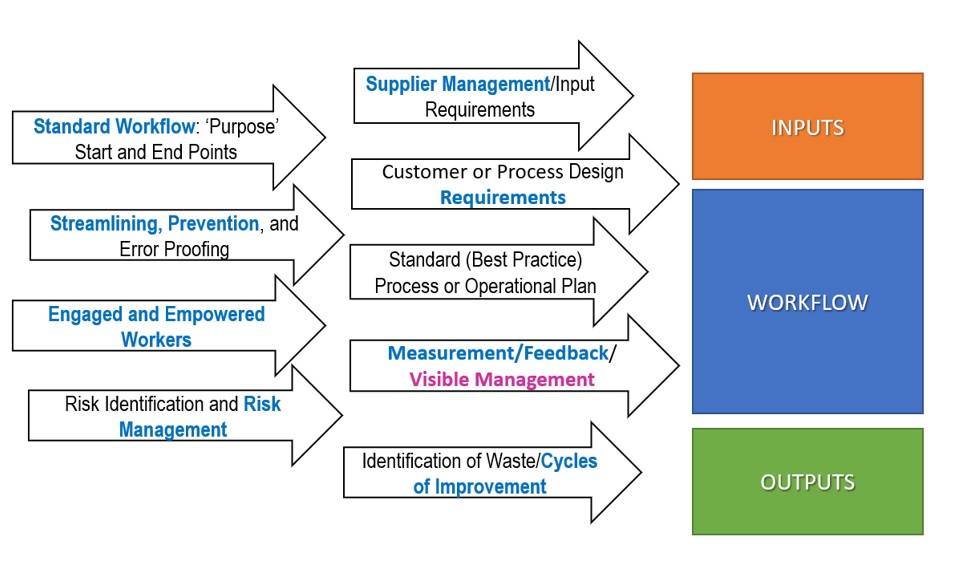

However, the beauty of accepting system management as a “real” but different discipline from process mapping, is its ability to immediately include every program office and front-line manager in its requirements for modeling and analysis. This is done by using the logic of a cause and effect diagram that is focused on positive effects and positive cause rather than on errors and error cause. If we look at the positive effect of an entire program office we will be describing its program purpose, and if we look at its causes we will be defining a best practice operational plan – the tasks and actions that most often create the positive result we have defined. From the point of view of the front-line manager, we are asking them to tell us “what it is you do here?” and the purpose of that activity. Then we have them build the interim steps (that milestones and check gates we will call “principal activity groups.)”[5] We will then ask them to create the tasks and actions (using a positive cause and effect) that will create success in each principal activity group. And lastly, we ask them to a set of measures and indicators that show they are completing those tasks and actions – which incidentally, are the leading measure of their unit success. If you consider the progression of actions above, you will find they conform to quality practice as much as they reflect “just good management.” So we have created a discipline that ensures organizational success and that no one can argue is “extra work” or does not make sense!

As this article can provide only a brief summary of the logic for structured system management, lets now take a quick tour of maturity modeling – for processes and systems. The ANSI G1 standard maturity models are based on measurable, observable, or verifiable aspects of quality operations, that derive from the functional area bodies of knowledge acknowledged by our quality profession. So for example, the Quality Management Principles of the ISO 9001 framework are one large source, as are the Core Values and Concepts of the Baldrige Excellence Framework. The key areas covered within the ANSI G1 maturity models are shown in the following figure:

It is widely recognized that successful quality initiatives in government do not ignite further similar initiatives, and that almost all such initiatives have a short life span. This was reported in the March 2017 research report of the ASQ Government Division, “Achievements and Barriers: The Results of Lean and Quality initiatives in Government.” https://my.asq.org/communities/reviews/item/155/12/2998 ISO 9001:2015 (at criteria 1.b) asks that organizations “enhance customer satisfaction through the effective application of the system, including processes for improvement of the system…” At criteria 0.3.1 the ISO standard says that its’ “process approach involves the systematic definition and management of processes…” However it offers only its process approach and DMAIC structure to document, control, or improve the system and its processes. Likewise the Certified Six Sigma Black Belt Handbook, Second Edition, states at page 10 that: “A business system is designed to implement a process or, more commonly, a set of processes…” None of the quality literature except ANSI G1 provides a means for structured documentation, analysis, and control of systems, except through process analysis.

The author has several extensive works showing the intellectual basis of systems, included in “Structured System Management: The Missing Link for Future Quality Practice”, Quality Management Forum, Summer, 2019. https://mallorymanagement.net/resources/, and also in “Lean System Management for Leaders”, https://www.routledge.com/search?kw=Lean+System+Management+for+Leaders pgs 7-18.

[4] Some further elaboration of use of the standard is provided in the pending publication: Mallory, R. (2022) Evaluating the Quality of Government Operations and Services: A Guide to Implementation of the ASQ/ANSI G1 Standard.

The ANSI G1 maturity models are then applied by trained “designated examiners” in each organization, to score the system (i.e. the quality structure of the program office) and any of its key processes, using measurable, observable, or verifiable aspects of quality derived from the best practices shown above. One important note here is that the maturity matrices use scores of from “0” to “5” to show the increasing use of acknowledged quality practices within the span of control of every manager and supervisor in an organization. Another important note is that the intent is to provide a uniform, objective, and visible score of the use of quality practice in every part of the organization, and to record that on an organization-wide scorecard. The System Maturity Model has four separate criteria, that are each scored from zero to “5”, depending on fulfillment of the criteria level descriptions. They include:

- System Purpose and Structure

- Goal Directedness through Goals and Feedback

- Management of Intervening Variables and Risk

- Alignment, Evaluation and Improvement

The Process Maturity Model has only three criteria, also scored from zero to ‘5’, as follows:

- Standard Process

- Measurements

- Process Improvement/ Employee Empowerment

Looking quickly at some specific criteria from maturity modeling, we can recognize that testing for the existence of measurable requirements (of the system or process) and of fact-based improvement cycles would provide two objective and verifiable criteria of the use of quality practice, even if at the lower levels. The existence of documentation of the workflow and tracking of its performance would be another distinguishing criteria. In addition, the existence of a “fact-based improvement cycle” will require that there first be a defined and repeatable method for learning and improvement, supported by some kind of feedback (if not formal measurement). If a manager is just using instincts or occasional comments from anyone as the basis of what needs to be fixed, it is not scientific and or fact-based. So to test the idea of fact-based problem solving we would ask: “How do you know what to work on?” and “Can you prove it is the right thing to work on?” If a manager has no data, the method of selection is not scientific and a positive result could not be proven.

Hopefully the reader will now recognize that our profession has overlooked a principal means of tracking the use of quality practice everywhere, which is found in the measurable, observable, and verifiable criteria of the process and system maturity matrices. (Why has the quality profession never developed these?) Likewise, perhaps the reader will better understand the assertion that we have ignored the best recognized approach to building quality in entire organizations because we have not been able to engage all front-line managers in its delivery.

The bottom-up nature of the ANSI G1 standard requires all work units to define their own best practice operational plan incorporating quality principles, and to then have them reviewed and scored. Further, all managers are asked to align and integrate their front-line operational plans with the high-level quality framework, also using the maturity models as a guide. We believe this standard also sets the stage for a visible organization-wide scorecard, that should motivate every front-line manager to ask the quality office for help, rather than the opposite – allowing the first ever “pull” system of quality improvement.

The ANSI G1 standard has been sponsored by the ASQ Government Division and is administered by its Center for Quality Standards in Government (CGSG). More information is available at https://my.asq.org/communities/blogpost/view/155/138/2631 or https://www.linkedin.com/showcase/center-for-quality-standards-in-government-cqsg/. It is the author’s hope that this article will pique your desire to learn more about the ANSI G1 standard, to request the Government Division sponsored training needed to become a Designated Examiner, and to join us in the effort of re-tooling quality practice for the 21st Century.

Please also note that the ANSI G1 standard is available for purchase from ASQ at https://asq.org/quality-press/display-item?item=T1574E, and that a workbook on Implementation of the ASQ/ ANSI G1 standard is now being readied for publication. Those interested in purchase of the workbook, or who would like to be notified of upcoming training can contact this author at the email address noted below. We invite government leaders everywhere to join in this effort.